An order management system (OMS) is supposed to bring order to chaos. In theory, it centralizes orders, synchronizes inventory, and ensures customers get what they bought, when they expect it. In reality, for many omnichannel businesses, the OMS becomes another layer of complexity. One more system teams depend on but don’t fully trust.

As brands expand across ecommerce, marketplaces, wholesale, and retail, order flows multiply. Each channel introduces different rules, fulfillment paths, and service-level expectations. What used to be a simple “receive order to ship order” process turns into a fragile web of dependencies across inventory, forecasting, procurement, and operations.

This is where most companies get stuck. They invest in an order management system expecting clarity and control, but end up with fragmented data, constant exceptions, and late decisions that drive stockouts, excess inventory, and unhappy customers. Understanding why this happens, and what an OMS can realistically solve. Is the first step toward building a system that actually scales.

What Is an Order Management System (OMS)?

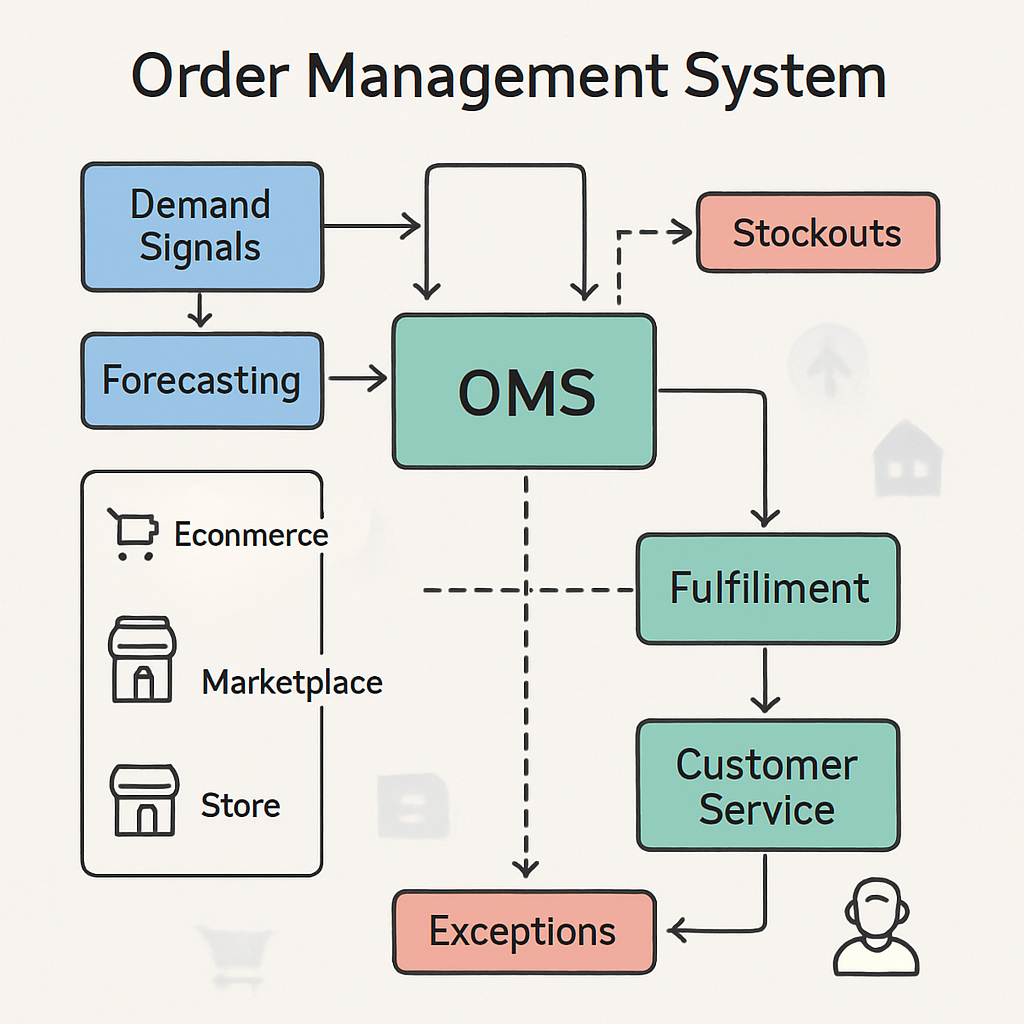

An order management system is the operational backbone that sits between demand and fulfillment. Its job is to capture, route, prioritize, and track orders across channels while coordinating inventory, warehouses, and delivery options. At its best, an OMS creates a single, consistent view of orders across the business.

Most teams adopt an OMS during a growth inflection point. Volumes increase, channels multiply, and manual coordination through spreadsheets or disconnected tools becomes unsustainable. The OMS promises structure: standardized workflows, fewer errors, and faster execution.

But defining what an OMS is and what it is not, is critical. Many problems blamed on “bad order management” are actually upstream issues related to demand signals, forecasting, and inventory decisions that no OMS alone can fix.

Going deeper on Order Management Systems

In practice, most order management systems focus on execution, not decision quality. They answer questions like:

- Where should this order ship from?

- Is inventory available right now?

- Which warehouse or store should fulfill it?

What they don’t answer well is why the system is constantly under pressure. When inventory is already misallocated, forecasts are unstable, or demand shifts are detected too late, the OMS becomes reactive. It spends its time rerouting orders, expediting shipments, and managing exceptions instead of enabling smooth fulfillment.

This creates a false sense of control. On dashboards, orders are flowing. On the ground, teams are firefighting:

- Inventory looks available globally but not where demand actually hits.

- Orders are split across warehouses, increasing cost.

- Service levels drop despite “healthy” stock on paper.

The core issue is that an OMS depends heavily on the inputs it receives. If demand signals are noisy, assumptions are unclear, or inventory targets are poorly set, the OMS faithfully executes flawed decisions at scale.

The real role of this system

To understand the real role of an order management system, teams need to position it correctly within the planning stack:

- Clarify the OMS scope: Define what the OMS owns (order capture, routing, status) versus what belongs upstream (forecasting, inventory policy, replenishment logic).

- Stabilize inputs before execution: Ensure demand signals, forecasts, and inventory targets are consistent and explainable before they reach the OMS.

- Reduce exception-driven workflows: High exception rates are a signal of upstream decision failure, not OMS misconfiguration.

- Measure decision latency, not just fulfillment speed: Late reactions to demand shifts force the OMS into constant override mode.

- Connect OMS performance to inventory outcomes: Track how order routing decisions contribute to stockouts, excess, and service-level volatility.

When the OMS operates on top of trusted, timely inputs, it becomes a force multiplier. Without that foundation, it simply accelerates existing problems.

An order management system is essential—but it is not a silver bullet. Its effectiveness depends entirely on the quality of demand, forecast, and inventory decisions feeding into it. Without that alignment, even the best OMS will struggle to deliver predictable outcomes.

Why Order Management Systems Fail at Scale

Most order management systems work well, until they don’t. Early on, when order volumes are manageable and channels are limited, an OMS delivers exactly what teams expect: visibility, coordination, and fewer manual errors. The cracks start to appear as complexity compounds.

Growth changes the nature of order management. New channels, new SKUs, faster delivery promises, and tighter margins all increase the cost of being wrong. At this stage, failures are rarely caused by missing features inside the OMS itself. Instead, they emerge from structural misalignment between planning and execution.

Understanding why order management systems fail at scale is critical, because many companies respond by adding more rules, overrides, and manual controls. This can make the problem worse instead of better.

Houston, we have a problem.

At scale, an OMS becomes a pressure amplifier. Any weakness upstream, forecasting, inventory allocation, assumptions, or demand interpretation shows up immediately in order flows.

Common failure patterns include:

- Inventory looks sufficient, but orders can’t be fulfilled efficiently: Stock exists, but not in the right location, channel, or packaging configuration.

- Exception rates explode: Teams rely on manual overrides to keep service levels acceptable, increasing operational risk.

- Costs rise faster than revenue: Split shipments, expedited freight, and suboptimal routing quietly erode margins.

- Trust in the system declines: When planners and operators can’t explain why the OMS made a decision, they stop relying on it.

The root cause is not poor execution logic. It’s poor decision inputs. An OMS executes rules faithfully, even when those rules are based on outdated assumptions or noisy demand signals.

Reducing failure in Order Management Systems

To prevent OMS failure at scale, teams need to shift focus from execution tuning to decision quality:

- Identify where overrides originate: Frequent overrides point directly to broken planning assumptions.

- Quantify the cost of exceptions: Track how often order routing decisions increase cost or delay delivery.

- Align inventory targets with real demand behavior: Static targets break quickly in volatile environments.

- Shorten feedback loops: Detect demand shifts early enough to adjust before orders are affected.

- Create explainability across systems: Every OMS decision should be defensible, not just technically valid.

When order management failures are treated as planning signals, and are not treated as operational annoyances, teams regain control without adding complexity.

Order management systems fail at scale not because they can’t execute, but because they are asked to execute decisions that no longer reflect reality. Fixing the upstream decision layer is the only sustainable path forward.

Order Management System vs Inventory and Forecasting Systems

One of the most common sources of confusion in supply chain technology is the overlap between order management, inventory management, and forecasting systems. Each plays a distinct role, but when boundaries blur, accountability disappears.

Companies often expect their OMS to “solve inventory problems” or “fix forecast misses.” When that doesn’t happen, they add more logic inside the OMS, routing rules, buffers, priority flags, without addressing the real gaps. This creates brittle systems that work only under stable conditions.

Clear separation of responsibilities is essential for scalable operations.

An order management system answers how orders should be executed. Inventory and forecasting systems answer what should exist, where, and when. When these layers are misaligned, friction is inevitable.

Typical symptoms of misalignment include:

- Orders routed correctly according to rules, but still arriving late.

- Inventory technically available, but functionally unusable.

- Forecasts updated after damage is already done.

The mistake is treating execution as a decision-maker. An OMS should not decide demand, inventory policy, or replenishment strategy. It should execute them.

Without a reliable forecasting and inventory layer:

- The OMS becomes reactive.

- Teams debate symptoms instead of causes.

- Planning credibility erodes across finance, ops, and leadership.

Stack Structure for order management system

High-performing teams structure their stack deliberately:

- Forecasting defines expected demand: By SKU, channel and time. The team must continuously update as signals change.

- Inventory systems translate forecasts into targets: Safety stock, reorder points, and allocation logic are set with clear assumptions.

- The OMS executes against those decisions: Routing, fulfillment, and order status follow trusted inputs.

- Feedback flows upstream: OMS outcomes inform forecast and inventory adjustments, not manual workarounds.

- Governance connects the layers: Assumptions, changes, and trade-offs are visible across teams.

This separation creates resilience. When demand shifts, planning adjusts before execution breaks.

An order management system is only as strong as the planning systems behind it. When forecasting and inventory decisions are clear and trusted, the OMS becomes a stabilizer instead of a stress point.

Where Flieber Fits in the Order Management Stack

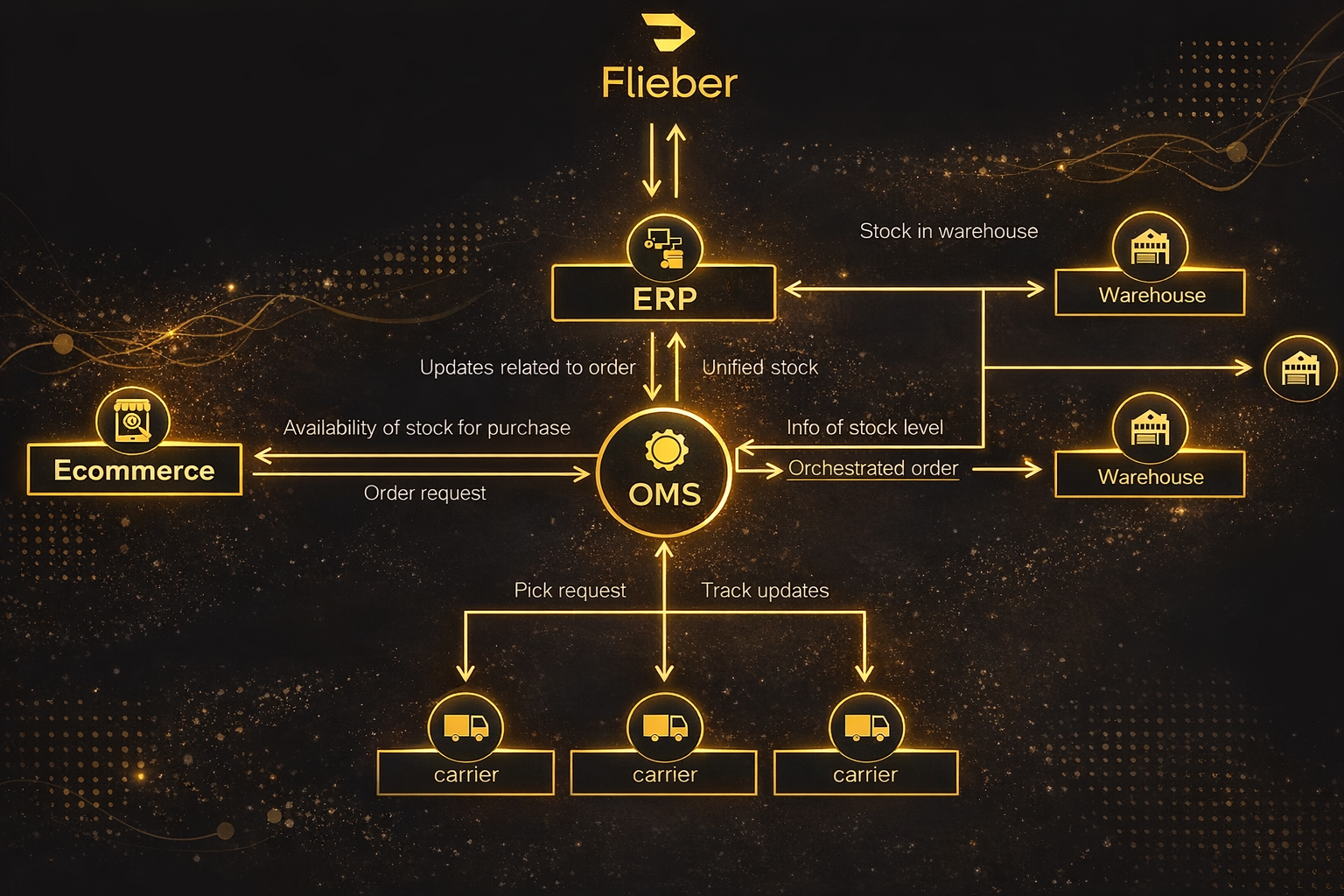

At first glance, modern order management architectures look deceptively simple. Ecommerce platforms capture orders, the OMS orchestrates fulfillment, and warehouses and carriers execute. The diagram often suggests a clean, linear flow from demand to delivery.

But this view hides a critical gap: decision-making. Most failures in order management don’t happen because orders aren’t routed correctly. They happen because the system is executing decisions that were already wrong before the order was placed.

This is where Flieber fits in. Flieber is not as another execution layer, but as the decision layer that shapes what the OMS is asked to execute.

In a traditional architecture, ecommerce sends an order request to the OMS. The OMS checks availability, applies routing rules, and triggers fulfillment. On paper, this looks efficient.

In reality, the OMS is constrained by upstream assumptions:

- Where inventory was allocated

- Which channels were prioritized

- How demand was interpreted

- What trade-offs were accepted between service level and cost

When those assumptions are outdated or wrong, the OMS enters permanent exception mode, rerouting orders, splitting shipments, expediting freight, and increasing cost. The OMS is not failing. It is faithfully executing flawed decisions.

This is why placing Flieber “between ecommerce and OMS” would be misleading. Flieber does not intercept orders or replace routing logic. Instead, it ensures that before orders ever hit the OMS, demand, forecasts, and inventory decisions already reflect reality.

A more accurate way to think about Flieber’s role is as an upstream decision layer that operates before execution begins. Ecommerce platforms capture raw demand signals through orders, traffic patterns, promotions, and channel-specific behavior. These signals reflect what is happening in the market, but on their own they are fragmented, noisy, and often misleading when interpreted at face value.

Flieber sits upstream to interpret and contextualize this demand. Instead of treating every spike or drop as actionable, signals are cleaned, explained, and classified as either short-term noise or structural change. This context is critical for distinguishing real demand shifts from temporary distortions caused by promotions, stockouts, or channel mix changes.

Based on this clarified demand picture, Flieber supports forecasting and inventory decisions. Forecasts are continuously updated, planning assumptions are explicitly versioned, and inventory outcomes, such as stockouts, excess, or service-level trade-offs. Those are simulated before any execution takes place. This ensures that decisions are made with foresight rather than hindsight.

With these decisions in place, the order management system can execute with clarity. Order routing, fulfillment, and orchestration run on trusted inputs, reducing the need for manual overrides, exceptions, and last-minute interventions. The OMS is no longer compensating for uncertainty upstream; it is executing decisions that already reflect reality.

Finally, execution feedback flows back into the decision layer. OMS outcomes inform better future planning, closing the loop between decision and execution. Instead of triggering constant firefighting, execution becomes a source of learning that continuously improves forecast accuracy, inventory positioning, and overall operational stability.

Flieber is not an order management system. Also it is not a replacement for one.

It is the decision intelligence layer that ensures order management systems operate on correct, timely, and defensible inputs. When Flieber is in place, the OMS stops compensating for uncertainty and starts executing with confidence.

Flieber sits upstream of the OMS, making demand, forecast, and inventory decisions clear, so order management actually works.

How to Choose an Order Management System for Omnichannel Scale

Choosing an order management system is rarely about features. Most modern OMS platforms can capture orders, route them, and track fulfillment. The real question is whether the system will hold up when your business scales across channels, regions, SKUs, and volatility.

For omnichannel brands, the cost of choosing the wrong OMS shows up quietly: higher fulfillment costs, constant overrides, declining service levels, and teams spending more time explaining exceptions than improving outcomes. Selecting the right system requires evaluating not just what the OMS does, but what assumptions it depends on.

Many OMS evaluations focus on surface-level capabilities, like: Number of integrations,

routing rules, UI dashboards and automation features.

These matter, but they don’t determine success. At scale, OMS failures are driven by misaligned inputs, not missing buttons. The most common mistake is choosing an OMS that assumes:

- Stable demand

- Static inventory targets

- Clean, reliable upstream data

In reality, omnichannel environments are volatile. Promotions spike demand unexpectedly. Channels grow at different speeds. Inventory flows shift across warehouses and regions. When an OMS isn’t designed to absorb that volatility, teams compensate manually by eroding the value of the system.

When evaluating an order management system for scale, high-performing teams look beyond feature checklists and focus on how the system behaves under real operational pressure. The first requirement is input dependency awareness.

A scalable OMS must clearly surface which decisions are driven by forecasting and inventory systems, rather than silently executing flawed inputs. When bad data or outdated assumptions are masked, execution appears functional while underlying problems compound.

Another critical factor is exception transparency. Teams need immediate visibility into why an order required intervention, not just the fact that it did. Without clear explanations, exceptions turn into recurring fire drills, and operational teams lose trust in the system’s logic.

Cost-aware execution is equally important. Routing decisions should make trade-offs explicit, showing how service-level improvements impact fulfillment cost. Systems that optimize blindly for speed often push hidden costs downstream, eroding margins while giving the illusion of strong performance.

Scalability under volatility is where many OMS platforms break. A system that performs well only under steady-state conditions will struggle as demand shifts, channels expand, or promotions distort normal patterns. True scalability means consistent behavior even when inputs change rapidly.

Finally, effective OMS platforms create feedback loops to planning. Execution outcomes must inform upstream forecasting and inventory decisions, closing the gap between planning and reality. When this feedback is missing, teams remain trapped in reactive execution instead of continuously improving decision quality.

An OMS selected with these principles becomes an execution engine. Not a bandage for broken planning.

The right order management system doesn’t eliminate complexity. It reveals it early, before cost, service, and trust break down.

Where Order Management Ends and Decision Intelligence Begins

Order management systems are designed to execute decisions. However, in volatile, omnichannel environments, execution is rarely the true bottleneck. The real constraint is decision timing and confidence. When demand changes quickly and complexity increases across channels, the cost of making the wrong decision, or making the right decision too late. It becomes far more significant than execution speed itself.

This is where many teams hit a ceiling. They invest in more sophisticated OMS tools, add layers of rules, and increase automation, yet still struggle with recurring stockouts, excess inventory, and constant escalations. The issue is not a lack of execution logic. What’s missing is decision intelligence upstream is clarity on what should be executed in the first place.

Execution systems inherently assume that key inputs are already correct. They assume demand has been interpreted accurately, forecasts are trustworthy, inventory targets reflect reality, and trade-offs between service, cost, and risk are understood and accepted across the organization. As long as these assumptions hold, execution can run smoothly.

When those assumptions break, the OMS does exactly what it was designed to do: it faithfully executes flawed decisions at scale. Teams then respond reactively by overriding orders, expediting shipments, or manually reallocating inventory. Over time, this pattern erodes trust not only in the system, but across operations, finance, and leadership, as results become harder to explain and defend.

The real failure in these scenarios is not operational. It is decision latency. Demand shifts are detected too late, assumptions are neither documented nor versioned, and inventory consequences are not simulated before commitments are made. By the time execution reveals the problem, options are already limited and expensive.

Without a decision layer that clearly explains what changed, why it matters, and what to do next, order management becomes permanently reactive. Execution systems are left compensating for uncertainty instead of delivering predictable outcomes, and teams remain stuck in a cycle of firefighting rather than improvement.

High-performing omnichannel teams separate responsibilities clearly:

- Decision intelligence interprets demand: Signals are contextualized, anomalies explained, and structural shifts identified early.

- Forecasting translates decisions into expectations: Forecasts update continuously, with clear ownership and assumptions.

- Inventory planning simulates outcomes: Stockouts, excess, and service-level trade-offs are visible before execution.

- OMS executes with confidence: Orders flow smoothly because inputs are trusted and timely.

- Feedback improves the system: Execution outcomes refine future decisions instead of triggering firefighting.

This structure turns order management into a stabilizer. It's not a stress point. Order management systems execute decisions. Decision intelligence ensures those decisions are worth executing.

An order management system is essential for omnichannel scale—but it cannot compensate for unclear demand signals, unstable forecasts, or poorly governed assumptions. The brands that scale sustainably are the ones that invest upstream, so execution becomes predictable instead of reactive.

If your order management system is constantly in exception mode, the problem likely isn’t execution. It’s decision quality.

Flieber helps omnichannel teams understand demand shifts early, build forecasts they trust, and make inventory decisions before outcomes lock in. Order management finally works the way it should.

👉 See how Flieber supports better order decisions upstream of your OMS.

FAQ — Order Management System

What is an order management system?

An order management system (OMS) is software that captures, routes, and tracks customer orders across channels while coordinating inventory and fulfillment.

Why do order management systems fail at scale?

Most OMS failures are caused by poor upstream inputs, unclear demand signals, unstable forecasts, and misaligned inventory targets rather than execution logic.

Is an order management system the same as inventory management?

No. Inventory management defines what stock should exist and where. An OMS executes orders using those decisions.

Can an OMS prevent stockouts?

An OMS can route orders efficiently, but preventing stockouts requires early demand detection and accurate inventory planning upstream.

How does omnichannel complexity affect order management?

Multiple channels increase routing decisions, fulfillment paths, and trade-offs. It makes upstream decision quality critical.