Inventory management software has become a standard part of running an e-commerce or retail operation. It promises visibility, control, and efficiency. And at a certain stage, it delivers exactly that.

But as brands grow, something changes.

The Hidden Cost Behind “Smart” Business Decisions

Opportunity cost is the reason “good decisions” still produce bad outcomes. In a real e-commerce business, you rarely choose between a good option and a bad option. You choose between two good options that compete for the same limited resource: cash, time, headcount, inventory capacity, warehouse space, or attention. The moment you commit to one path, you give up the upside of the path you did not take. That forfeited upside is not a theoretical concept. It is often the biggest cost in the decision, and it rarely shows up on a *P&L.

P&L (Profit and Loss) is a financial statement that summarizes a company’s revenues, costs, and expenses over a specific period. It shows whether the business is operating at a profit or a loss and is used to evaluate financial performance and profitability.

Most operators underestimate opportunity cost because they only measure what is visible. They see the explicit cost of a decision: the invoice, the payroll, the ad spend, the shipping bill, the software subscription. But the largest impact is frequently invisible: what the same resources could have produced if deployed elsewhere.

This is especially true in e-commerce and retail, where inventory is one of the largest uses of capital and one of the hardest to reverse. Buying inventory is not just “getting stock.” It is converting flexible cash into a non-flexible asset that must be sold, stored, insured, and managed. If you buy the wrong quantity, the wrong SKU mix, or buy at the wrong time, the consequence is not only carrying cost or markdowns. The consequence is everything you could not do because your capital got trapped.

That is why opportunity cost is not an academic finance term. It is a decision-quality lens. It helps explain why companies with strong revenue can still struggle with cash flow, why brands can have “healthy inventory” but still miss growth windows, and why teams can work harder while getting less leverage from the same resources.

If you run a business with constraints (and every business does), opportunity cost is always present. The only question is whether you are pricing it into your decisions or paying it later.

To turn opportunity cost into an advantage, you need a simple operating habit: every meaningful decision should be compared to the next best alternative using the same unit of measure.

In practice, that means:

- Name the constrained resource you are spending (cash, inventory capacity, time, ad budget, warehouse space).

- List the best real alternative you would do if you did not choose this option (not a fantasy option, a real one).

- Estimate outcomes for both options using the same metric (profit, contribution margin, cash impact, or expected return).

- Include timing and risk, because an option that returns later or is less reliable may be less valuable even if it looks larger on paper.

- Decide intentionally, knowing what you are giving up.

This is the mental model that separates businesses that “optimize locally” from businesses that allocate resources strategically.

Opportunity cost is the price of committing resources.

You do not eliminate it. You either measure it upfront or pay it later.

Once you see it clearly, decision-making stops being reactive and starts becoming capital-efficient.

What Is Opportunity Cost? A Practical Definition for Business

Opportunity cost is the value of the best alternative you give up when you choose one option over another. In plain English, it is what your business could have gained if you had used the same resources differently. It applies to money, time, labor, inventory capacity, and even attention. If resources are limited, opportunity cost exists.

The biggest misconception is thinking opportunity cost is only about money. It is not. It is about constraint.

A business decision is rarely “Can we do this?” The real question is “What does this prevent us from doing?” Because:

- Cash spent here cannot be spent elsewhere.

- Time spent here cannot be spent elsewhere.

- Inventory space used here cannot be used elsewhere.

- Warehouse labor used here cannot be used elsewhere.

Opportunity cost also becomes more important as the business grows, because constraints tighten. Growth increases complexity: more SKUs, more channels, longer lead times, more promotions, more moving parts. In that environment, the cost of misallocation rises fast.

Here are a few common examples where opportunity cost is the real driver of outcomes:

- Inventory: Buying extra units “just in case” can feel safe, but it may prevent you from buying fast movers, funding marketing during peak demand, or reacting to a trend.

- Marketing: Spending your budget on low-margin SKUs may lift revenue while reducing profit and starving higher-return channels.

- Operations: Keeping fulfillment in-house may reduce per-unit cost but consume leadership time and slow down expansion.

- Product: Launching feature A may delay feature B that would have reduced churn or improved conversion.

Opportunity cost turns “what seems cheaper” into “what is actually better.” It forces decisions to be evaluated against alternatives, not in isolation.

A practical way to identify opportunity cost is to look for decisions that create a “hidden trade”:

- Any decision that locks resources

Inventory purchases, long-term contracts, hiring, tooling changes, channel expansion. If it is hard to undo, opportunity cost is high. - Any decision that competes with growth capacity

Warehouse throughput, customer support capacity, procurement bandwidth, content production, engineering cycles. - Any decision that changes optionality

Optionality is the ability to respond to surprises. When you burn optionality, opportunity cost increases because you lose the ability to choose better paths later.

Use this rule of thumb: If a decision makes your business less flexible next month, opportunity cost deserves explicit attention today.

Opportunity cost is not an “extra” concept. It is the core of resource allocation.

Once you train your team to ask “what are we giving up,” decisions become sharper, faster, and less emotional.

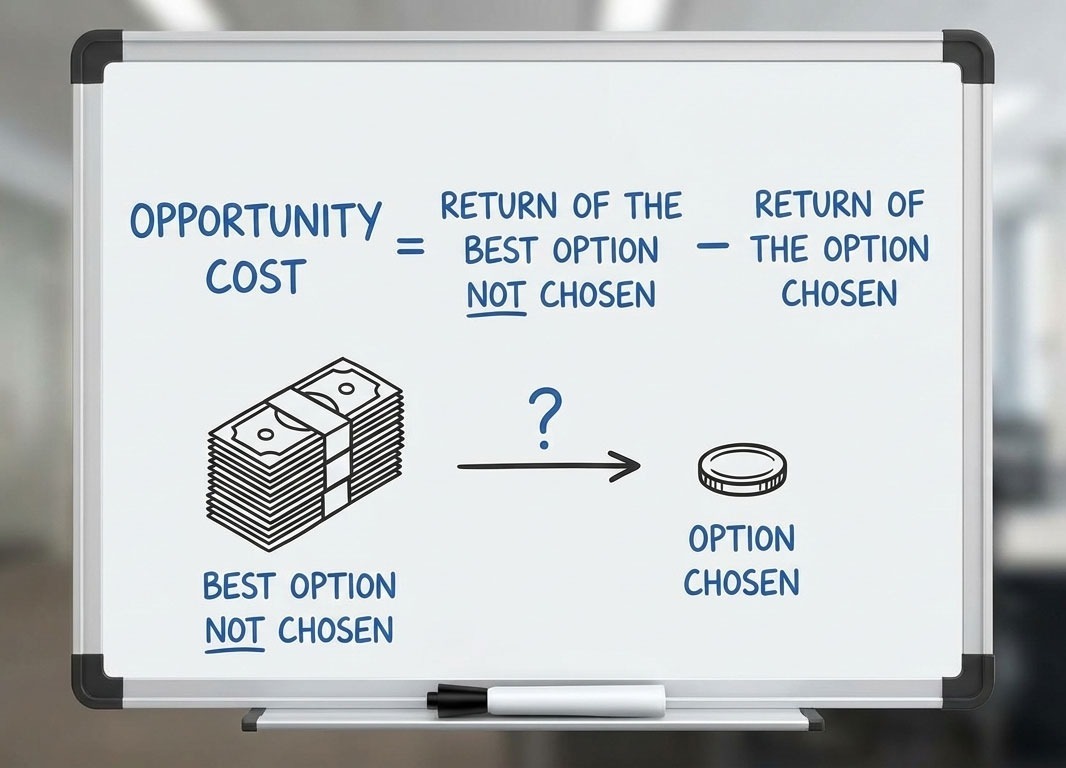

Opportunity Cost Formula: How to Calculate It Without Fooling Yourself

The cleanest way to calculate opportunity cost is simple subtraction:

Opportunity Cost = Return of the best option not chosen − Return of the option chosen

That is it. The complexity is not the math. The complexity is defining “return” correctly. Most opportunity cost calculations fail for one of three reasons:

- Comparing different types of returns

Teams compare revenue in one option to profit in another. Or they compare short-term profit to long-term strategic value without a common unit. That creates false confidence. - Ignoring timing

A return in 12 months is not equal to a return in 30 days, especially in fast-moving commerce. Cash velocity matters. Seasonality matters. Lead times matter. - Ignoring hidden inputs

A decision might look good until you include what it consumes: operational workload, carrying cost, risk of markdowns, customer experience impact, supply chain uncertainty, and the fact that stockouts hide true demand.

If you want a calculation that actually helps, you need to define return in a way that matches the decision.

Here is a reliable approach used in real operating decisions:

Step 1: Pick the “return” metric that fits the decision

Common choices:

- Contribution margin (profit after variable costs) for product, pricing, promotions.

- Cash impact for inventory buys, payment terms, financing decisions.

- Expected profit (profit × probability) for uncertain outcomes.

- Time-to-value when speed matters (peak seasons, launches).

Step 2: Build two scenarios: chosen option vs. best alternative

Not ten options. Just the best alternative you would realistically do.

Step 3: Estimate returns using the same time window

A 90-day inventory bet should not be compared to a 12-month initiative without adjusting for timing. Keep the window consistent.

Step 4: Subtract and interpret

The difference is your opportunity cost.

A concrete e-commerce example (inventory-capital trade-off)

A brand has $200,000 available to deploy. They are deciding between:

Option A: Buy deeper inventory for a broad set of SKUs “to reduce stockout risk.”

Expected impact over 90 days: +$40,000 contribution margin (but higher carrying cost risk).

Option B: Concentrate that same capital on hero SKUs with the highest velocity and margin, and support them with marketing timed to peak demand.

Expected impact over 90 days: +$70,000 contribution margin (with better sell-through).

Opportunity cost of choosing Option A is:

$70,000 − $40,000 = $30,000 over 90 days.

And that is before you factor in secondary effects like:

- fewer markdowns from long-tail overbuying

- less storage pressure

- more predictable availability during campaigns

- cleaner demand signals (fewer stockout-driven data distortions)

This is why opportunity cost matters so much in inventory. Inventory does not only cost money. It determines what your money can do next.

The opportunity cost formula is simple. The discipline is not.

If you define returns consistently and include timing, you stop optimizing “cheap” choices and start choosing high-leverage ones.

Opportunity Cost vs. Sunk Cost: The Mistake That Quietly Destroys Returns

One of the most common and expensive decision-making errors in business is confusing opportunity cost with sunk cost. The two are often mentioned together, but they should never be treated the same way. When they are, companies end up doubling down on bad decisions instead of reallocating resources toward better ones.

Understanding this distinction is essential because inventory, marketing, and operational decisions are full of sunk costs. And *sunk costs create emotional and organizational inertia.

Sunk cost is a cost that has already been incurred and cannot be recovered. Because it cannot be changed by future decisions, it should not influence whether to continue, change, or abandon an investment or course of action.

A sunk cost is a cost that has already been incurred and cannot be recovered. Money already spent, inventory already purchased, time already invested.

An opportunity cost is the value of the best alternative you give up from this point forward.

The rule is simple but hard to apply:

Sunk costs should never influence future decisions. Opportunity costs should.

This mistake shows up everywhere:

- A brand keeps promoting a low-performing SKU because “we already bought the inventory.”

- A team maintains a complex internal process because “we’ve already invested too much time building it.”

- A company continues using a tool that no longer scales because “we already paid for the annual contract.”

In all of these cases, the decision is anchored in the past instead of evaluated based on future returns. The correct question is not “What have we already spent?” It is “Given where we are today, what is the best use of our resources from here forward?”

A practical way to eliminate sunk cost bias is to force a reset in your evaluation:

Ask this question explicitly: “If we had not already made this decision, would we choose it again today with the same information and constraints?”

If the answer is no, continuing is not conservative. It is expensive.

Opportunity cost is always forward-looking. Sunk cost is always backward-looking. Mixing them guarantees capital inefficiency.

Sunk costs explain the past. Opportunity costs determine the future. Only one of them should guide decisions.

Why Opportunity Cost Is Especially Critical in Inventory Decisions

Inventory is one of the most misunderstood uses of capital in business. It feels tangible, safe, and operationally necessary. But from a financial perspective, inventory is frozen optionality. Once cash becomes stock, it loses flexibility.

That is why opportunity cost is nowhere more impactful than in inventory decisions.

Inventory has three characteristics that make opportunity cost particularly dangerous:

- It is capital-intensive

Inventory absorbs cash upfront. That cash cannot be redeployed until the inventory sells, and sometimes not even then if markdowns are required. - It is slow to correct

If demand changes, you cannot instantly undo an inventory decision. Lead times, storage, and fulfillment constraints create long feedback loops. - It distorts data when mismanaged

Stockouts hide true demand. Overstocking inflates storage and discounting noise. Both corrupt future forecasts, compounding opportunity cost over time.

This is why two brands with the same revenue can have radically different financial outcomes. The difference is not sales volume. It is how inventory capital is allocated.

- Buying breadth instead of depth

Capital spread thin across many SKUs often underfunds the products that actually drive revenue and margin. - Buying early instead of buying precisely

Purchasing inventory too far ahead of demand increases carrying costs and reduces flexibility if trends shift. - Protecting availability everywhere instead of where it matters

Trying to avoid stockouts across the entire catalog often leads to excess inventory on low-velocity SKUs.

In each case, the explicit cost is visible. The opportunity cost is what hurts more: the growth that could have been funded, the campaigns that could have scaled, or the risk that could have been avoided.

High-performing teams treat inventory as deployed capital, not as a safety blanket.

They ask:

- Which SKUs deserve capital based on velocity and margin?

- Where does one additional unit create the highest incremental return?

- What inventory should not exist, even if it feels operationally “complete”?

This is how opportunity cost becomes a strategic lens instead of a theoretical one.

Inventory decisions are never neutral. They either accelerate growth or quietly suppress it. Opportunity cost is the difference.

Opportunity Cost, Capital Efficiency, and ROIC

Opportunity cost becomes truly powerful when connected to capital efficiency. This is where operational decisions translate directly into financial performance. One of the clearest ways to see this connection is through Return on Invested Capital (ROIC).

ROIC measures how efficiently a business turns invested capital into operating profit. Inventory is one of the largest components of invested capital in e-commerce and retail. That makes opportunity cost a primary driver of ROIC, whether teams track it explicitly or not.

When opportunity cost is ignored, ROIC suffers in predictable ways:

- Excess inventory increases invested capital without increasing profit.

- Misallocated inventory lowers contribution margin through markdowns.

- Capital locked in slow movers cannot be used to fund high-return initiatives.

The result is a business that grows revenue but destroys efficiency. From the outside, it looks like progress. From a capital perspective, it is stagnation.

How opportunity cost improves capital efficiency

When opportunity cost is priced into decisions, inventory stops being measured only in units and starts being measured in returns.

That changes behavior:

- Capital flows toward high-velocity, high-margin SKUs.

- Inventory buffers become dynamic instead of static.

- Decisions are evaluated based on expected return, not fear of stockouts.

This directly improves ROIC by:

- Reducing idle capital

- Increasing profit per dollar invested

- Preserving optionality during uncertainty

Inventory as a capital allocation problem

At scale, inventory planning is not an operational task. It is a capital allocation problem under uncertainty.

Opportunity cost forces one critical question: “Is this the best use of our capital right now?” Teams that consistently answer that question well outperform teams that simply “stay in stock.”

ROIC is not improved by working harder. It is improved by allocating capital better. Opportunity cost is the lens that makes that possible.

Opportunity Cost in Demand Forecasting: The Cost of Being “Almost Right”

Demand forecasting is often treated as a statistical exercise. If the forecast is “close enough,” teams feel confident. But opportunity cost exposes a deeper truth: a forecast can be numerically accurate and still be strategically wrong.

This happens because forecasting is not just about predicting demand. It is about deciding how much risk to take, how much capital to commit, and how much optionality to preserve.

Every forecast implies a commitment. When a business forecasts demand, it is implicitly deciding:

- How much inventory to buy

- When to deploy capital

- Which SKUs deserve priority

- How aggressively demand can be stimulated

If the forecast overestimates demand, capital is locked into inventory that produces diminishing returns. If it underestimates demand, revenue is suppressed, campaigns underperform, and customer trust erodes.

The opportunity cost is not the forecast error itself. It is the alternative reality that could have been captured with a better allocation of capital.

Small forecasting errors do not scale evenly. A 10% mistake on a low-margin, slow-moving SKU may have minimal impact. That same error on a high-velocity product during a peak period can trigger a cascading chain of consequences, from stockouts at the worst possible moment to emergency replenishment costs, lost customer lifetime value, and distorted demand signals that corrupt future planning. Forecasting errors are rarely symmetric. In practice, the downside almost always outweighs the upside.

Instead of asking “What is the most likely demand?”, high-performing teams ask:

- What is the cost of being wrong on the upside?

- What is the cost of being wrong on the downside?

- Where does one additional unit of inventory create the highest expected return?

This reframes forecasting as a decision problem, not a prediction problem.

A forecast is not valuable because it is accurate. It is valuable because it leads to better decisions under uncertainty. Opportunity cost is the metric that reveals whether it does.

Opportunity Cost in Marketing and Growth Decisions

Marketing teams rarely lack ideas. They lack inventory readiness.

In growing e-commerce businesses, the most expensive growth mistakes happen when marketing decisions are made without accounting for opportunity cost in inventory and capital.

Common scenarios include:

- Scaling paid media because ROAS looks strong, while inventory coverage is fragile

- Running promotions to “move stock” that could have sold at full price later

- Pushing demand evenly across the catalog instead of concentrating on capital-efficient SKUs

In each case, growth appears positive in isolation. But the opportunity cost reveals the hidden damage.

When marketing ignores opportunity cost:

- Ads drive traffic into low availability, increasing CAC without increasing revenue

- Promotions cannibalize future full-price demand

- Capital is burned accelerating low-return SKUs instead of amplifying high-return ones

The missed opportunity is not just the campaign that failed. It is the campaign that could have worked better if capital and inventory had been allocated differently.

At scale, marketing is not just a demand generator. It is a capital amplifier.

Every dollar spent on marketing multiplies the impact of inventory decisions. If inventory is well-positioned, marketing compounds returns. If inventory is misallocated, marketing accelerates inefficiency.

This is why opportunity cost must sit between marketing and inventory planning.

Growth is not about pushing harder. It is about pushing where it pays. Opportunity cost tells you where that is.

Opportunity Cost in Operations and Supply Chain Decisions

Operational decisions are often justified in the language of efficiency. Lower unit costs, tighter utilization, shorter handling times, better margins. On the surface, these improvements look unequivocally positive. But in complex supply chains, every operational optimization carries an opportunity cost that rarely appears on dashboards.

Choosing a cheaper supplier with longer lead times may reduce cost per unit, but it also removes the ability to respond quickly when demand shifts. Consolidating shipments lowers transportation expenses, yet it increases rigidity precisely when responsiveness matters most. Maximizing warehouse utilization improves efficiency metrics, but often at the expense of speed, surge capacity, and service levels during peak periods. Each of these decisions improves one visible metric while quietly degrading another dimension of performance.

This is where opportunity cost accumulates in operations. Long lead times amplify forecast risk, because errors must be absorbed over a longer horizon. Reduced flexibility limits the organization’s ability to react to demand spikes, market shifts, or unexpected disruptions. Aggressive cost optimization can unintentionally increase revenue risk by making inventory slower, scarcer, or misallocated when it matters most.

The impact of these trade-offs is rarely immediate. They surface later, often at the worst possible moment. Demand accelerates, but inventory cannot move or replenish fast enough. Trends shift, yet capital is locked into products ordered months ago. Service levels decline during critical windows, damaging customer trust and long-term value. In hindsight, the real cost of the original decision becomes clear: the business traded away agility in exchange for localized efficiency.

Mature operators understand that operational excellence is not about minimizing cost in isolation. It is about balancing efficiency with optionality. Instead of asking only how much cheaper a decision is, they ask how much flexibility it removes, which revenue opportunities become unreachable, and how fragile the system becomes if assumptions break. They recognize that resilience has economic value, even if it does not show up as a line item.

Opportunity cost is the lens that makes this visible. It measures not just what was saved, but what was made impossible. In modern supply chains, efficiency without flexibility is not strength. It is fragility disguised as optimization.

Why Teams Systematically Underestimate Opportunity Cost

Most teams don’t ignore opportunity cost on purpose. They underestimate it because it is structurally invisible.

Traditional metrics reward what happened, not what could have happened. Revenue, margin, inventory turnover, and forecast accuracy all look backward. Opportunity cost lives in the alternative timeline, the decisions not taken, the growth that never materialized.

Why do the same mistakes always happen?

There are three structural reasons opportunity cost is underestimated:

First, success bias. When a decision “works,” teams stop questioning alternatives. The fact that a result was acceptable becomes proof that it was optimal.

Second, siloed incentives. Marketing is rewarded for growth, operations for efficiency, finance for cost control. Opportunity cost sits between these functions, so no one owns it explicitly.

Third, false precision. Forecasts, dashboards, and models create the illusion that uncertainty is controlled. When numbers look exact, teams forget to ask whether the underlying assumptions are fragile.

Each small underestimation compounds. Capital gets trapped incrementally. Risk accumulates quietly. Over time, the organization becomes slower, more conservative, and less responsive, even while metrics appear healthy.

Opportunity cost is not ignored because it is complex. It is ignored because it is uncomfortable. And because no dashboard highlights it by default.

A Practical Framework to Evaluate Opportunity Cost in Business Decisions

Understanding opportunity cost conceptually is not enough. Teams need a repeatable way to evaluate it before decisions are locked in.

The goal is not perfect precision. The goal is structured comparison.

Before committing capital, inventory, or effort, high-performing teams consistently ask:

- What alternative uses of this resource exist right now?

This forces visibility. Inventory, cash, and time always have competing uses, even if they are not obvious. - What is the expected return of each option under realistic assumptions?

Not best case. Not the worst case. Realistic base scenarios. - What happens if assumptions break?

This is where most plans fail. Opportunity cost grows exponentially when forecasts are wrong. - Which option preserves the most optionality?

Flexibility has value. The option that keeps more paths open often wins long term, even if short-term returns look similar.

This framework works across:

- Inventory buys

- Marketing investments

- Hiring decisions

- Supply chain choices

- Product launches

The key is consistency. Opportunity cost only becomes visible when comparisons are made explicitly and repeatedly.

Opportunity cost does not require complex math. It requires disciplined comparison.

How Software Changes Opportunity Cost Economics

Opportunity cost has always existed. What has changed is whether businesses are able to see it early enough to influence the outcome, or only recognize it after capital has already been committed.

For decades, opportunity cost was largely a retrospective concept. Teams made decisions based on static plans, historical averages, and simplified assumptions. Only later, once inventory was purchased, campaigns launched, or capacity allocated, did the true trade-offs become visible. By then, the cost of the alternative path was already locked in.

Traditional operational systems reinforce this lag. Most software is designed to record transactions, not to evaluate decisions. It excels at documenting what happened after the fact: what was sold, what was ordered, what inventory remains. What it does not do is model alternative futures, simulate uncertainty, or expose trade-offs before decisions are made. As a result, opportunity cost is discovered too late, when reversing course is expensive or impossible.

Modern planning and forecasting software fundamentally changes this dynamic. Instead of treating demand, supply, and capital as fixed inputs, advanced platforms model them as uncertain variables. They allow teams to explore multiple futures before committing resources. Scenario modeling makes it possible to ask not just what is most likely to happen, but what could happen if assumptions break.

When systems can simulate outcomes such as demand exceeding forecast by 20 percent, lead times slipping unexpectedly, or capital being reallocated toward higher-velocity SKUs, opportunity cost stops being theoretical. It becomes visible in concrete terms: lost revenue, increased risk, delayed growth, or constrained optionality. Decisions can then be compared not just on expected outcomes, but on downside exposure and resilience.

This shift changes how teams operate. The question is no longer “What happened?” but “What should we do next, given the trade-offs we see now?” Opportunity cost becomes a decision input, not a post-mortem insight. Capital-aware recommendations surface the real cost of choosing one path over another before the choice is finalized, rather than after its consequences are felt.

Software does not eliminate opportunity cost. Scarcity still exists, and trade-offs remain unavoidable. What modern systems determine is timing. They decide whether opportunity cost is something you proactively manage with foresight, or something you pay for later with regret.

Where Flieber Fits: Turning Opportunity Cost Into Executable Decisions

Understanding opportunity cost conceptually is not the hard part. The real challenge is operationalizing it before decisions are locked in.

This is where most teams struggle. They know inventory ties up capital. They understand forecast risk. They see the trade-offs in hindsight. But without the right decision layer, opportunity cost remains abstract. It is discussed in meetings, debated across teams, and discovered only after the consequences materialize.

Flieber exists to close that gap.

Flieber is not an inventory management system and it is not an ERP. It is a decision intelligence platform built specifically for inventory-driven businesses operating under uncertainty. Instead of focusing on what happened, Flieber focuses on what should happen next, given demand variability, lead times, and capital constraints.

By modeling demand probabilistically at the SKU and channel level, Flieber makes opportunity cost visible before capital is committed. Teams can see how allocating inventory to one SKU, channel, or time window affects revenue, cash flow, and risk compared to the next best alternative. This transforms opportunity cost from a theoretical concept into a concrete decision input.

Rather than optimizing inventory in isolation, Flieber evaluates inventory as deployed capital. It helps teams answer questions traditional systems cannot:

- Which SKUs deserve capital right now, and which do not?

- Where does one additional unit generate the highest expected return?

- When should demand be accelerated, and when should it be intentionally constrained?

- How much downside risk does a forecast error create, and where?

This is especially critical in environments with long lead times and volatile demand, where mistakes compound over months, not days. By stress-testing scenarios before purchases are made, Flieber allows teams to preserve optionality, avoid capital traps, and align inventory, marketing, and operations around the same economic reality.

In practice, this means fewer reactive decisions, less capital locked in slow movers, and more confidence when pushing growth during peak periods. Opportunity cost stops being something teams explain after the fact and becomes something they actively manage.

Flieber does not eliminate trade-offs. No software can. What it does is ensure those trade-offs are explicit, comparable, and priced into decisions early enough to matter.

Opportunity Cost as a Competitive Advantage

Every e-commerce company operates under the same fundamental constraints. Capital is finite. Time is limited. Attention is scarce. What separates average operators from exceptional ones is not access to better resources, but the discipline with which those resources are allocated.

Opportunity cost is the lens that makes this discipline visible. It forces decision-makers to confront not only whether a choice is profitable in isolation, but whether it is the best possible use of capital, time, and organizational focus at that moment. This shift in perspective is subtle, but transformative.

High-performing operators do not ask whether a decision makes money. They ask what becomes impossible once that decision is made. They compare every initiative against all other alternatives competing for the same capital. As a result, inventory stops being treated as a passive buffer and becomes a deliberate growth lever. Marketing is no longer about generating traffic, but about amplifying returns on constrained inventory. Operations move beyond cost minimization and become a form of structured risk management, designed to preserve flexibility under uncertainty.

When opportunity cost is evaluated consistently, its effects compound quietly. Capital efficiency improves because fewer resources are trapped in low-return uses. Forecasting errors become less damaging because decisions account for uncertainty instead of assuming precision. Growth becomes more predictable because inventory, marketing, and operations are aligned around shared trade-offs rather than competing objectives. Over time, the business develops resilience that is difficult for competitors to observe or replicate.

This is why opportunity cost is not merely an economic or accounting concept. It is the hidden architecture behind every meaningful business decision. Companies that ignore it often grow until they collide with invisible constraints they cannot explain. Companies that master it scale with intention, allocating resources with clarity even when the future is uncertain.

In volatile markets, opportunity cost is not a limitation. It is the strategic signal that reveals where growth is real, where risk is acceptable, and where restraint is the most powerful move available.